Photographing The End: The Skyline As Necropolis

Life is nothing but instability and disequilibrium…a tumult, continuously on the verge of explosion. -Georges Bataille, from “Erotism: Death & Sensuality.”

What perfect equilibrium. Stability. Certainty. What perfect equanimity. These are some of the qualities one may see when he or she looks at a photograph of a city skyline. Or, one may see a massing of buildings, a tour de force of architecture. Or one may see the essence of New York City. Or one might see death biding his time.

Roland Barthes, in Camera Lucida, Reflections on Photography (1981), writes, “A specific photograph is, in effect, never distinguished from its referent (what it represents) …” 1 In this paper, I will look at this particular subset of urban photography to see what is represented and also what is concealed.

The most notable aspect of skyline photography is distance. From the photographer’s point of view, the greater the distance between the camera and its subject, the more dramatic the photograph will appear—the greatest number of buildings, the highest degree of congestion. From the “spectator’s” (to borrow another of Barthes’ terms) perspective, distance ensures the maximum experience of tension, rising from the picture’s frame. However, the role of physical distance suggests to me another kind of distance, and that dimension is what I will explore in the following pages.

One always views a skyline from a “safe” distance. Safe, in this context, means that one is invited to experience the thrill of the city without either identifying with it—with its fate—or exposing oneself to the danger inherent in the place itself.

The idea of safe viewing should not be confused with voyeurism. The voyeur’s eye is aggressive, and the pleasure he or she finds in a subject under his or her scrutiny is always subordinate to the frisson found in the act of looking. There is always some transgression, some violation, associated with the voyeur; but the spectator of the skyline’s motives is more conventional, even innocent. The skyline is ultimately seen as a document; often acquired as a souvenir. It is an image one can and does send home to mother.

The skyline, like every photograph, is by design and nature incomplete. (See Ill.1)

As we saw above, we are obliged to provide its meaning. A conventional reading of a skyline is concerned with the surface—the physical attributes of a city at a particular time. While aspects of history, architecture or city planning may dominate one’s immediate impressions, these are not of much interest to me. What concerns me is the utopian vision inherent in this genre. It boosterism. It’s ideology of immortality.

Skyline photography not only suggests a glorious past and a vibrant present, but also a promise of a brilliant future—a world beyond the reach of death.

What’s more, these photographs implicate us in this utopian vision of urban life. The question I will explore in the following pages is: What else would we see if we were willing to look beneath the surface?

Seeing the City

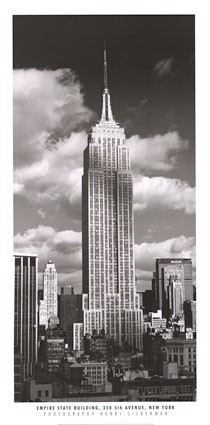

There are many ways to photograph the City. The most popular include portraits of its inhabitants: Men and women captured either as individuals or in groups, in the course of the everyday. Men and women as archetypes or “characters.” This distillation of place to the life of its inhabitants confirms the human presence at the heart of these great, and frequently shifting, piles of stone, steel and brick. Another way to create the urban sense of place is to capture exceptional events, preferably something that reveals or hints at a darker feature of the city. These include fire or crime scenes. Still another is reproductions of iconic images that advance any number of social or cultural constructs. The most compelling of these, in my opinion, are images of The Empire State Building. (See Ill.2)

Images of this building, perhaps more than any other, define our idea of the 20th Century urban phenomenon. All of our culture’s dreams, fears and ambitions seem to find expression in this towering structure. Transformed by time and media, it is more an icon than a viable office building. All of which suggests that any photograph of this building will present the spectator with a myriad of complementary and contradictory impressions. Too much ambiguity. Too much unsaid. Which is to say, you cannot really see this building only at a glance.

Why ambiguity? Because history—even, especially, recent history—has taught us cities are not eternal. Great cities can and do die. They are susceptible to explosion, implosion and erosion.

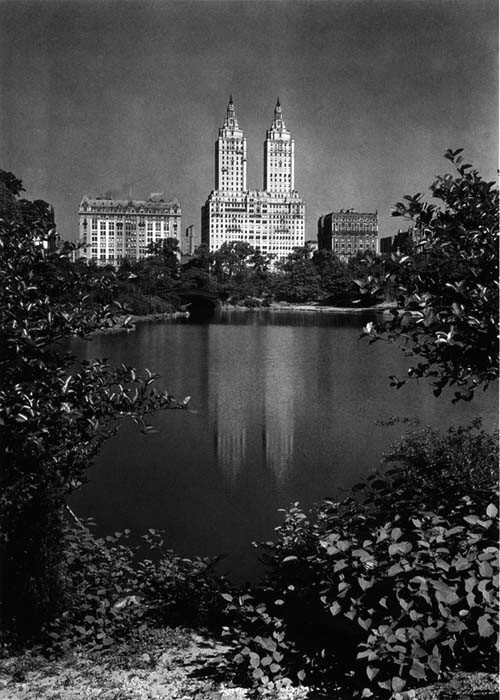

Some cities, such as Rome following the fall of the Empire, and Hiroshima in the aftermath of the Second World War, can be resurrected. (See Ill.3) Others, from Pompeii and Machu Picchu to the ruins of ancient cities of the Mesopotamia and along the Silk Road, have never recovered, whether invaders or desertification toppled their towers.

Was this the face that launched a thousand ships,

And burnt the topless towers of Ilium?

Sweet Helen, make me immortal with a kiss.2

Cities are vulnerable, and those who inhabit them are vulnerable. But for some reason, we pretend they/we aren’t. We will accept that cities evolve, grow or diminish in importance. We experience this firsthand when a place important to us loses its lease or is demolished to make way for progress. We may even mourn the loss of a building, a neighborhood, even a restaurant, and feel that absence as much as the loss of a loved one. But that a city, one’s own city, can be obliterated—this must be repressed. So, of necessity, we claim a uniqueness, a dispensation, and deny such a possibility, despite ample photographic evidence to the contrary—from coffee table books of Angkor Wat to photographs documenting the fall of Berlin, 1945. (See Ill. 4) As Freud made clear in his essay On Transience, “The mind recoils from anything that’s painful.” The thought that one’s city can be destroyed is too unacceptable to consider, even as we entertain the fantasy that death is an event that happens to others.

Nothing Is Only What It Seems

Up to this moment I have referred to the “city” in the general sense of the word, but I will, from this point on, be referring to New York City in particular.

Whatever it is that photographers capture in a skyline, they do not capture the City. One can imagine from street photography the sounds of the City, its reverberations, its perpetual expansions and contractions. In contrast, almost every skyline suggests a depopulated city. A dead city. A Necropolis.

The living City represented by the street photographers—from Stieglitz and Steichen, Hine and Weegee (Arthur Fellig), to Bourke-White, Abbott, Frank and Klein—gave us our image of the modern City. Through their work we not only make sense of the place, but also find the words and emotions to express our experience of it. One learns from these photographs what it means to be a New Yorker.

In some ways, these images of the City that we take for granted are the products of a historical accident— New York’s growth neatly corresponded with the advent and expansion of mass media. So much so, I am tempted to argue that the City was created as much by media as by its famous industries and architecture. And what we think of as natural to the place was in fact defined by the limits of various media techniques and technology.

Nevertheless, a skyline photograph of New York must be considered a different class of artifact than street photography. A different kind of symbol, working to communicate a different kind of meaning. In some ways, it serves a similar purpose as the prints, paintings and models created and reproduced as souvenirs for travelers on the Grand Tour. Those representations of Naples with Vesuvius smoking in the background, and the canals of Venice, drew a line between the past and the present day. In effect saying: This is where you come from but it is not who you are. But in another, more important way, skyline photography contradicts the earlier message by erasing this line, and merging different eras and peoples to promote a vision of the City that’s predicated on unbroken continuity. In this sense, all skyline photographs, whether taken at the turn of the last century or created last week, are obliged to represent the City as unchanging, even immortal.

Once and Future City

Changes to the City’s skyline are understood as minor, seen more as a matter of style than substance. This is because while individual buildings are themselves discontinuous, the skyline is a blending, a fusion of many individuals, into what Bataille might call a single and continuous mode of existence. 3

In this way, additions and subtractions are relatively unimportant, an almost impersonal, certainly unconscious, accumulation. (See Ill.5) The fact is, Times Square is the once and future Times Square. The Empire State Building remains the epitome of the skyscraper regardless of what is raised in Shanghai or Dubai, or over the footprint of the former World Trade Center. The skyline is Manhattan and all that it suggests, reveals and, most importantly, conceals.

As we saw above, the skyline photograph does not so much memorialize as perpetuate a utopian vision. These images are part of a publicity machine that releases only happy news (from the short stories of O. Henry and Damon Runyon, non-stop to episodic TV, Seinfeld and Friends). As popular fiction, cinema, the Law & Order franchise and a hundred years of photography confirm: Each new generation of New Yorkers is merely the latest generation. In the same way, each new building is merely a latest feature on the skyline.

Skyline photography perpetuates this fiction, supplying a portrait of an urban Shangri La, within a formal aesthetic—often black and white photography, always, as we saw above, from a distance. As Rem Koolhaas observed: “The metropolis strives to reach a mythical point where the world is completely fabricated by man, so that it absolutely coincides with his desires.” With this in mind, photographers have succeeded in creating a representation that doesn’t really represent. Their achievement is to create not an image of a place, but the image of an idea of place. And, in this case, a place where death is absent, and the spectator is insulated from the facts of death.

If they are successful, it is because, as Errol Morris observed in his editorial “Not Every Picture Tells a Story,” “If we want to believe something, then we often find a way to do so… Believing is seeing and not the other way around.”5

That this City exists is a wonder in itself. I think E. B. White said this best when he wrote: “It is a miracle New York works at all. The whole thing is implausible.”6

But if one considers Bataille’s thoughts on transformative powers of work, then the City, particularly the City, as represented in skyline photography, was inevitable in man’s evolution. What’s more, as he observed, the point of work is that we desire, “to bring into the world found on discontinuity all the continuity such a world can sustain.”

New York is the physical expression, even celebration, of work. One might say that New Yorkers are the most human, if not humane, of the species, because of the exaggerated importance they place on work. A work ethic confirmed in the lyrics of the song, “New York, New York”: “If I can make it there, I’ll make it anywhere.”7

But this is the City, like all cities—from Sodom and Babylon to Paris in the ‘20s, Berlin in the ‘30s and London in the ‘60s—is where all taboos related to violence, sex and death are transgressed, and where the consequences are sometimes fatal or permanent, but always punishing.

Photographs of the skyline may shimmer with reflected sunlight, or when caught at night, sparkle and illuminate the sky; but like any city, at any time, it is vulnerable to attack from without, and rupture from within.

We have geared the machines and locked all

Together into interdependence; we have built the

great cities; now

There is no escape.

In spite of this eventuality, Bataille reminds us, in Erotism, that it is in the city with its myriad distractions and opportunities for pleasure, where we can live, by “assenting to life even in death,” and in this way challenge death “through our indifference to it.”

The Besieged City

Cast a cold eye on life, on death; horseman, pass by!” Epitaph on W.B. Yeats’ gravestone9

In Camera Lucida, Bathesidentifiestwo fundamental themes in a photograph: the studium and the punctum. The former, as I understand it, refers to those elements in the picture that relate to its cultural or shared meaning. These elements can be described as objective or as denotative as opposed to connotative.

The punctum, which Barthes defines as having the power to “disturb the studium,” is far less objective. As Margaret Olin noted in “Touching Photographs,” her critique of Barthes book, “the punctum is always personal to the viewer and often a detail.” Olin further clarifies Barthes’ division suggesting “a separation between mind and emotion, the scholarly versus the personal” respectively.10

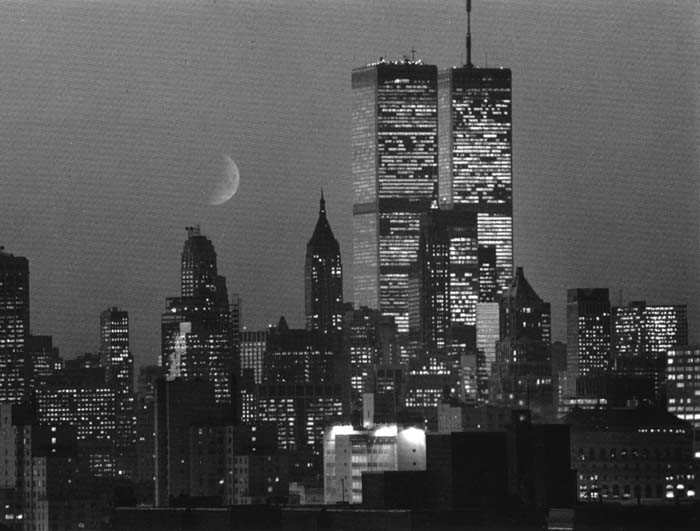

I will use these terms to examine a photograph of lower Manhattan taken by Jean Miele in 1987. (See Ill.6) When I first saw this image on a postcard, the Twin Towers were still, as I described at the very beginning of this paper, balanced, stable, certain. As such, the image’s studium contained a number of things that may or may not have interested me but were clearly in the photograph: I noted the presence of fifty years of architecture. I observed the moon. I even suspected the photographer’s intent, and my response were somewhat aligned.

But there was something in the photograph that, as Barthes described it, “pricked” me. What pricked me was a deceptive and illusory stillness and quiet. This sensation, which punctured the field, as Olin described it, was my punctum. (See Ill.6)

This photograph may once have offered a lovely, untroubled, representation of the City’s southern skyline; but as we’re all now aware, it is no longer representative. In the years since this photograph was taken, events have made the photographer’s original intent entirely beside the point. Miele could not have had any idea of what he either saw or captured. He may have been interested in documenting architectural evolution. Or, as likely, the sight of the moon over the City may have simply moved him to take the picture.

But time and events have transformed this image, and made it, and every other like it, something different. It is now impossible for me to look at this picture and not experience what Barthes referred to as a “shock.”

Not shock in the conventional, or even, appropriate sense, as in “I can’t believe these towers are gone.” But shock in the Barthian way, which is not a response to content or subject that” traumatizes,” but a personal feeling of dissonance that comes from suddenly seeing what was so well hidden. The implications of which are as affecting as they are subjective.

What was hidden in this photograph all along was the possibility, if not the inevitability, of the building’s demise. And by building, I mean the City of New York. The “shock” effect was not present in the original photograph, although one might have had a premonition, based on the image’s uncanny stillness. As if the skyline was waiting with an almost animal-like prescience, as when a hunted animal first catches the scent of a predator. Or it possessed the very quiet before the proverbial storm.

More likely not, as the original image conformed to the principle convention of skyline photography, which promotes the idea (and ideology) of continuity. It was the events of 9/11 that gave new meaning to Miele’s work; that transformed the image from a contemporary representation to a historical one. As a result, it no longer belongs with other representations of New York, but with historical artifacts, such as pictures of the Coliseum in Rome or the Mayan Pyramids of Teotihuacan.

As we saw earlier, the convention of the skyline photograph not only promotes but also requires continuity. The implication being: The City that’s whole today will be whole tomorrow. This was true about Miele’s photograph, but it is no longer true. Quite by accident, Miele’s photograph has broken the spell. Suddenly a skyline can suggest a different, less welcome kind of continuity, such as that presented by a ruin, or even a cemetery.

New York has always been represented as complete. Unlike Rome, where the entire history of the City is told in fragments and segments—

Rome

Old stone

On old stone

On old bone11

—the myth of New York is that of city born intact, whole, in motion. Even as new buildings replaced old and the skyline grew more variegated and climbed upward to greater heights and with ever-greater intensity, the true sense of place, the essence of the place, remained unchanged. As we saw above, photographers from Steichen up to Miele—performing an almost religious ritual—colluded in perpetuating an image of the City as impregnable.

But the shock—the lingering shock—I now experience from Miele’s photograph doesn’t come from the particular fact that the World Trade Center was doomed, but from the realization that the City, too, is doomed. The skyline is as porous as the Great Wall of China. This is something that weighed on E.B. White in 1948 and informed his little book Here is New York. Then, the menace was nuclear war with the Soviets. Today, we are haunted by a myriad of deaths, from anthrax, bird flu and dirty bombs to inundation, due to global warming.

Denying the Inevitable

New York is now a besieged City, but skyline photography continues to maintain the illusion that we are invulnerable. This threat is something we “sophisticates” now live with, even if we don’t acknowledge it.

I think it would be better if we did, and, not panic, but instead affected the élan shown by the Tuscan nobles in Boccaccio’s The Decameron, who took refuge in their country estates outside Florence to escape the plague that threatened it.

These handsome young men and beautiful young women did not so much deny what stalked them but made a game of their predicament. (They knew exactly what they were running from—death, the corruption of flesh, the horror of annihilation. And in a manner reminiscent of Bataille, they responded to death by giving themselves over to sensual pleasures.)

Unlike Boccaccio’s heroes and heroines, New Yorkers after 9/11 for the most part stayed put. I witnessed an extraordinary insouciance, a mass denial of recent events in the days immediately following. I had gone uptown to Etro to buy my wife a birthday gift. My visit to Madison Avenue happened to coincide with fashion week. The City was still crowded with celebrities, who could not return home to Paris or Milan. There, walking in front of me, were Anna Wintour, the editor of Vogue and the fashionista, Andre Leon Talley. Arm in arm they strolled, seemingly without worry in the world. The day was bright and inviting—as bright and inviting as on the day of the attack—and the outdoor tables at Nello’s were crowded with beautiful people. Me, I was shopping for cashmere, not emergency rations. I was, as Bataille might have observed, seeking to transcend the violence of death with luxe and sex.

As I compared this stretch of Madison Avenue with my own neighborhood, still closed to traffic and forbidden to all but residents, it occurred to me that one could, simply by turning one’s back on Ground Zero, deny the significance of the attacks on the City. As I emailed people the following day: “Uptown was more La Dolce Vita than Apocolypse Now.

It is not my intent to attribute any of this behavior to callousness, or indifference to the suffering of others. Rather to recall what Canetti, noted in Crowds and Power, “Survival is at the core of everything that we—rather vaguely—call power.” 12

In a curious way, this suddenly re-discovered power, aligned with the typical “feelings of superiority,” that is part and parcel of living in New York. It is what we use to make bearable the inconveniences and humiliations that we endure on a daily basis. However, what I wish to suggest is that for those of us who “survived,” one of two things may have happened: 1) We had come to terms with our mortality, or 2) We had managed to repress our fear of death entirely.

Fear of death is the raison d’être of the City. It is not merely a coincidence that a skyline resembles the palisades of a fortress. The skyline is a symbol of the defensive wall that separate the City from nature, which is to say, separates it from death. One could define the City as the ultimate repudiation of “nature.”

The myth of the City is that it allows us to believe that we exert complete control over external circumstances. Its very existence can be understood as a monument to our culture’s profound rebellion against reality—the reality of death. A futile protest against what David Lavery described as an ineluctable, “existential event.”13

In this sense, architecture is an immortality strategy. For all of us who think of Mother Nature closer to Medea than to Mary, the City’s hard surfaces and sharp edges are a comfort, protecting us from both named and unnamed anxieties. Our buildings, and all the cultural constructions they house, give us, as Becker would say, a means to transcend “the limits of morality.”14 Ultimately, the skyline photograph is a symbol for our individual and collective wish for immortality.

However, to my mind, the irony of this kind of photography, this kind of symbol, is the ways in which it represents the world’s most vital City—not as a vivid reality but as a place devoid of life. The City the skyline captures—still, eerie, passive— is more a necropolis than a thriving metropolis. It is a City that is either populated by ghosts or will be eventually.

In any event, it seems to me that the moment the skyline is reproduced as a photograph, it becomes an artifact, relic or symbol—as useful temporarily to the anthropologist as a hieroglyphic, to the interior decorator as a color swatch or the advertising art director as swipe art. But that as a representation will eventually be betrayed by time. Just as Miele’s photograph was by 9/11.

The affection I feel for the City, the pleasure I take in looking at photographs of this City, is underscored by a nostalgia that contains some of the qualities of mourning commented on by Freud in both “On Transience”and “Mourning and Melancholia.” I think it is impossible to look at a photograph of the City, and not come to the conclusion that one’s place, both figuratively and literally, is expendable. The most banal aspects of City life—every vacant apartment listing, every store opening or closing—remind one that he or she will certainly die. The people who inhabited the images that illustrated this paper, certainly the developers and architects of the buildings, are all likely to be dead now, or will be soon. Yet, these skylines continue to tell stories with themes of continuity, regeneration, in effect, they continue to promise immortality.

Becker, in The Denial of Death, speaks of two ontological motives—Eros and Agape. Both are central to the mythology of the City. On the one hand, the City invites the individual to define and assert his or her sense of self. What better opportunity to exercise one’s will, to stand out, to see one’s name in lights, than on Broadway, or in the precincts of the corner office, or in winning the rat race, or by climbing the ladder of success?

And, on the other, what better place to experience agape than in the famous crowds, that swell and rise like waves beneath those heights, behind those walls? Here, one may let go, abandon his or her will and find peace by merging into a bigger, more significant and enduring “beyond.”

The City is a man-made Beckian Beyond. A place to play out the “drama of one’s heroic apotheosis.” The skyline photograph may be a false promise, but it is a promise nonetheless, that says you can achieve either or both, in perfect safety, while hiding in plain sight, among the currently living and the soon to be dead.

Notes and Credits

Photo Credits

Illustration 1: Feniniger, Andreas, Lower Manhattan from Staten Island Ferry

Illustration 2: The Empire State Building

Illustration 3: Hiroshima Atomic Dome

Illustration 4: Temple of Ta Prohm, Angkor, Cambodia

Illustration: 5: Gottscho Samuel H, Rockefeller Center Under Construction, 1932

Illustration 6: Miele, Jean, Twin Towers with Moon, 1997

Illustration 7: Gottshco, Samuel H, San Remo Apartments, 1932

Notes

- Barthes, Roland, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (Trans. from French by Richard Howard). Hill and Wang, 1981

- Marlowe, Christopher. “The Face of Helen,” Dr. Faustus

- Bataille, Georges. Erotism: Death & Sensuality (Trans. from French by Mary Dalwood) CITY LIGHTS BOOKS, 1986

- Koolhaas, Rem, delirious new york The Monacelli Press. 1994

- Morris, Errol, “Not Every Picture Tells a Story,” The New York Times, November 20, 2004.

- White, E. B., Here is New York, With a New Introduction by Roger Angell, a New York Bound book, The Little Bookroom, New York, 1999

- Ebb, Fred & Kander, John, “New York, New York” (Originally theme song from Scorsese film, New York, New York), 1977

- Jeffers, Robinson, “The Purse-Seine,” 1937 (See whole poem below)

- Yeats, William B. “Under Ben Bulben” (Also the epitaph on is gravestone)

- Olin, Margaret, “Touching Photographs: Roland Barthes’s “Mistaken” Identification” in Representations: Fall 2002; 80, 1, pg. 99,

- Sawyer, Robert “Rome,” 2004

- Canetti Elias, Crowds and Power, (Trans. from the German by Carol Stewart) Continuum, 1962

- Lavery, David, “It’s not television, it’s magic realism: the mundane, the grotesque and the fantastic in Six Feet Under” in Reading Six Feet Under: TV to Die For, edited by Kim Akass and Janet McCabe, I.B. Tauris, 2005

- Becker, Ernest, The Denial of Death, Freepress Paperback/ Simon & Schuster, 1973

The Purse Seine

Our sardine fishermen work at night in the dark of the moon;

daylight or moonlight

They could not tell where to spread the net, unable to see the

phosphorescence of the shoals of fish.

They work northward from Monterey, coasting Santa Cruz; off

New Year’s Point or off Pigeon Point

The look-out man will see some lakes of milk-color light on the

sea’s night-purple; he points and the helmsman

Turns the dark prow, the motorboat circles the gleaming shoal

and drifts out her seine-net. They close the circle

And purse the bottom of the net, then with great labor haul it in.

I cannot tell you

How beautiful the scene is, and a little terrible, then, when the

crowded fish

Know they are caught, and wildly beat from one wall to the

other of their closing destiny the phosphorescent

Water to a pool of flame, each beautiful slender body sheeted

with flame, like a live rocket

A comet’s tail wake of clear yellow flame; while outside the

narrowing

Floats and cordage of the net great sea-lions come up to watch,

sighing in the dark; the vast walls of night

Stand erect to the stars.

Lately I was looking from a night mountain-top

On a wide city, the colored splendor, galaxies of light: how could

I help but recall the seine-net

Gathering the luminous fish? I cannot tell you how beautiful

the city appeared, and a little terrible.

I thought, We have geared the machines and locked all together

into interdependence; we have built the great cities; now

There is no escape. We have gathered vast populations incapable

of free survival, insulated

From the strong earth, each person in himself helpless, on all

dependent. The circle is closed, and the net

Is being hauled in. They hardly feel the cords drawing, yet they

shine already. The inevitable mass-disasters

Will not come in our time nor in our children’s, but we and our

children

Must watch the net draw narrower, government take all powers

-or revolution, and the new government

Take more than all, add to kept bodies kept souls- or anarchy,

the mass-disasters.

These things are Progress;

Do you marvel our verse is troubled or frowning, while it keeps

its reason? Or it lets go, lets the mood flow

In the manner of the recent young men into mere hysteria, splin-

tered gleams, crackled laughter. But they are quite wrong.

There is no reason for amazement: surely one always knew that

cultures decay, and life’s end is death.